by the government because it was part of the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Ran

ge which was established i

n

1942. The se

Field Laboratories

Continuing Education Credit

cluded Jornada

del Muerto was

p

erfect as it provi ![]()

ded isolation for secrecy

- and safety, but was still close to Los A

- lamos for easy commuting back and forth. (Building the test site) In the fall of 1944 soldiers started arriving at Trinity Site to prepare for the test. Marvin Davis an

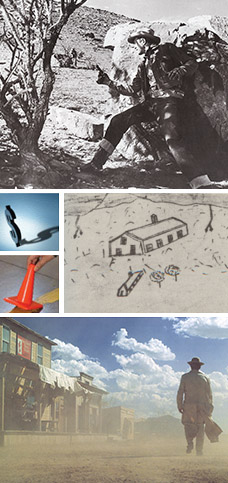

- d his military police Sgt. Marvin Davis with police horses Argo and Peergo at basecamp. unit arrived from Los Alamos at the site on Dec. 30, 1944. The unit set up security checkpoints aro

- und the area and had plans to use horses to ride patrol. According to Davis the distances were too great so they resorted to jeeps and trucks for transportation. The horses were sometimes used for polo, however Davis said Capt. Howard Bush, base camp commander, somehow g

- ot the men real polo equipment to play with but they preferred brooms and a soccer ball. Oth

er recreation a

- t the site included volleyball and hunting. Davis said Capt. Bush allowed the soldiers with experience to use the Army rifles to hunt deer and pronghorn. The meat was then cooked in the mess hall. Leftovers went i

- nto soups which Davis said were excellent. Of course, some of the soldiers were from cities and unfamiliar with being outdoors a lot. Davis said he

- went to relieve a guard at the Mockingbird Gap post and the soldier told Davis he was surprised by the number of "crawdads" in the area considering it was so dry. Davis gave the young man a quick less

- on on scorpions and warned him not to touch. Throughout 1945 other personnel arr

- ived at Trinity Site to help prepare for the test. Carl Rudder was inducted into the I Camp engineers (from Sgt. Carl Rudder's scrap book) are labeled: 1st

- row--Kilmer, Frenchie, Bontley, Leary, Spry, Raub, Kemp, Stockton and Rauldolph. 2nd row--Gorden, Cox, Harrison, King, Bres, Sigler, Matthews, "Weadle-W

- alve" and Capt. Gueary. A view of the east side of base camp. In the left foreground is the Dave McDonald ranch house, not to be confused with the George McDonald ranch where the bomb's core was assembled. Army o

- n Jan. 26, 1945. He said he passed through four camps, took basic for two days and arrived at Trinity Site on Feb. 17. On arriving he was put in charge of what he called the "East Jesus and Socorro Light and Water Company." It was a one-man operation --himself. He was responsible

- for maintaining generators, wells, pumps and doing the power-line work. A friend of Rudder's, Loren Bourg, had a similar experience. He was a fireman in civilian life and ended up trained as a

- fireman for the Army. He worked as the station sergeant at Los Alamos before being sent to Trinity Site inApril1945. In a letter Bourg said, "I was sent down here to take over the fire prevention and fire

- department. Upon arrival I found I was the fire department, period." As the soldiers at Trinity Site settled in they became familiar with Socorro. They tried to use the water out of the ranch w

- ells but found it so alkaline they couldn't drink it. In fact, they used Navy saltwater soap for bathing. They hauled drinking water from the fire house i

Gasoline Accord

ing to Raemer Schreiber, Robert Bacher was the advisor and Marshall Holloway and Philip Morrison had overall responsibility. Louis

- Slotin, Boyce McDaniel and

- Cyril Smith were responsible for the mechanic

- al assembly in t

- he ranch house. Later Holloway was responsib

le for the mechanical assembly at the tower. In the afternoon of the 13th the core was taken to ground zero for insertion into the bomb mechanism. The bomb was assembled under the tower on July 13. The plutonium core was inserted into the device with some difficulty. On the first try it stuck. After letting the temperatures of the plutonium or contact Leslie Griego at 1-866-476-9333, or email and casing equalize

id smoothly into p

lace. Once the

Performance Level

assembly was complete many of the men took a welcome relief and went swimming in the water tank east of the McDonald ranch house. The next morning the entire bomb was

- raised to the top of the 100-foot

- Improvised explosive devices (IEDs)

- steel tower

- and placed in a small shelter. A crew then attached all the detonators and

by 5 p.m. it was complete. The 1 00-foot steel tower at ground zero.